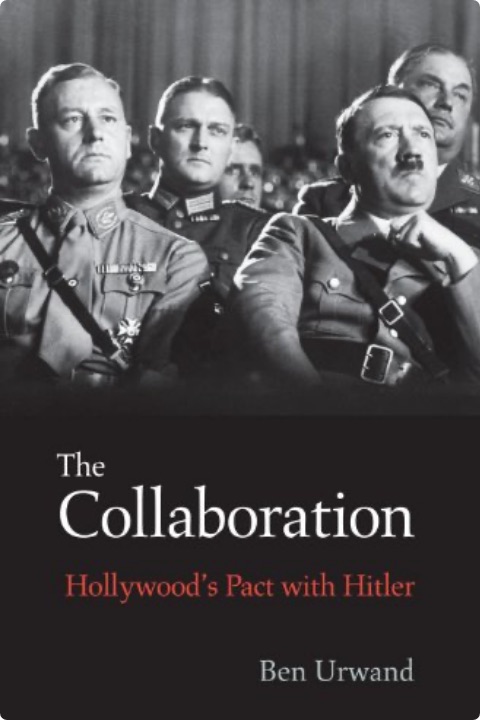

At the recent Austin Film Festival, at every ruminative panel or round-table discussion I attended, I slapped my copy of this book down in front of me. The cover, I felt, was bound to catch the eye of the screen legends and louche suits from the big production companies. Above the uncompromising title, it shows a photograph of Adolf Hitler watching a movie with his entourage, his stern, blunt features palely lit by the glowing screen, his mouth small, his nostrils flared in concentration. What, one wonders, was he watching? Laurel and Hardy? Mickey Mouse?

Ah, Christmas with Hitler. One can imagine the songs, the pranks, the endless games of Battleships.

Another of several surreal juxtapositions to be found in Ben Urwand’s dedicated, deadpan study of his subject is the sheer seriousness that Germans brought to their appreciation of film comedy in the 1930s: their competitive dismay at the edge that American movies had over theirs. ‘We are unable to make films like this, in which silliness is everything,’ lamented one critic of the 1934 comedy Forsaking All Others. ‘A new victory in American humour,’ another conceded of 1936’s Desire. Meanwhile, Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night(1935), starring Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, was hailed by Goebbels himself as ‘A funny, lively American film from which we can learn a lot. The Americans are so natural. Far superior to us.’

The main flaw of these movies, in Urwand’s eyes, was that many of them neglected or flouted the ideals of Nazism. Not all of them, however. And here we reach the crux of his thesis: namely that the moguls of Hollywood ‘collaborated’ with the Nazis in some kind of ‘pact’ to cut their films to please, or rather not to displease, the officers of the Third Reich. This last distinction is important. There’s a big difference, unacknowledged by the author, between editing a finished film to placate German censors, which the Americans did, and crafting it from scratch to promote a Nazi message, which they didn’t. The production houses were businesses. They wanted to continue making money in the German market, which meant kowtowing to a regime that, as became increasingly obvious, was murderous. The levels of guilt increase as you go forward in time; you might equally say they decrease as you go backward. But the author has no sliding scale.

Some of the evidence Urwand has dug up makes for queasy reading. There’s the 1938 letter to Hitler’s secretary from the Berlin branch of 20th Century Fox, signing off with, ‘Heil, Hitler!’ (Urwand doesn’t say, as he should, that this was a wholly conventional way to end such a letter in those days). There was the reluctance of Jews in the industry to make movies about what was then called ‘the Jewish problem’, in case it should seem like special pleading: a disastrous decision, in retrospect. There were the contortions by which the American companies permitted to stay in Germany after 1936 — Paramount, 20th Century Fox and MGM — got around a law that prevented them from taking money out of the country: in the cases of the first two, by filming newsreels of Nazi rallies and selling it abroad; in that of the third, by loaning it to German arms manufacturers in return for bonds, which they could then export.

Yet there’s little sign here of the author having thought deeply about how shame and blame work, about the difference between motive and effect, say, and the primacy of the former in judging the morality of individuals. He remarks that other countries made particular demands of Hollywood — Britain, for example, boycotted religious films — but he doesn’t dwell on it. He notes in passing that other companies, including IBM and General Motors, put ‘profit above principle’ in their dealings with Germany in the 1930s. To which one is tempted to say: plus ça change.

‘Collaboration’ is the word Urwand has chosen for his title, on the grounds that it (or rather, its German equivalent, Zusammenarbeit) crops up repeatedly in the correspondence between the film-makers and the censors. Yet it wouldn’t then have carried the connotation it acquired post-Vichy, for example. A similar point could be made about his co-opting of the word ‘pact’ into his subtitle. This is language geared towards making people feel, rather than think — the traditional stratagem not of the historian, you might say, but the film-maker. Or, perhaps, the propagandist.