Anyone for Tennessee? At a best guess, the answer to that’s yes. There’s scarcely a moment these days when there isn’t a Williams play on somewhere in the West End or along the Great White Way.

One reason for this is that he wrote such succulent roles, and I don’t mean just his steamroller leads, though for a kind of bruised or brittle actress, Blanche Dubois is as close to a female Hamlet as it gets. In A Streetcar Named Desire, there’s also the surly stud Stanley; Stella, his sex-drunk bride; and the courtly, perspiring Mitch, bewitched by Blanche’s blend of magic.

Then think of The Glass Menagerie, which has the smothering mother Amanda, the crippled Laura, and the conflicted Tom, who abandons both to pursue his vocation as an author. When it debuted in 1944, the play caused a sensation comparable to that of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House 50 years earlier: an ode to the liberation of youth, as Doll’s House was of women, daring to present its theme in all its glaring selfishness.

Think of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof’s sizzling Maggie, and its sozzled Brick, waiting for the ‘click’ from that last drink which will bring him the Zen of deep drunkenness; or the Rev T. Lawrence Shannon in The Night of the Iguana, another sonorous, anti-amorous drunk, forever thirsting to take ‘the long swim to China’ that would solve all his problems.

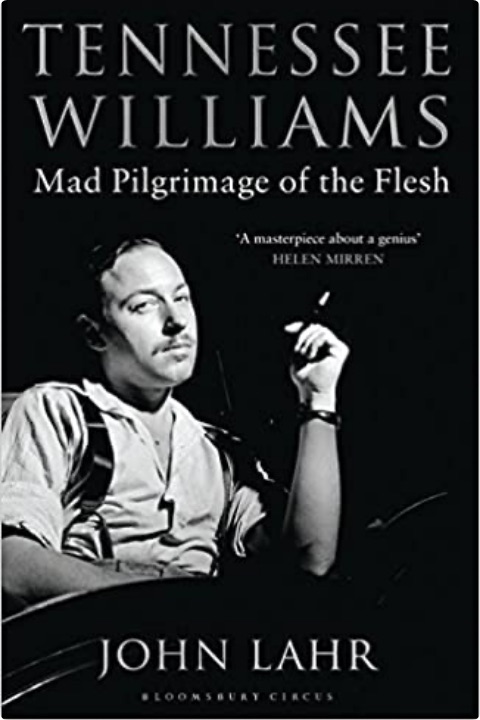

Still popular, still important. Which makes it all the more surprising that, 31 years after the playwright’s suicide, there hasn’t yet been a definitive biography. This is the throne to which John Lahr’s book aspires, and the pre-publication clamour is promising. ‘A masterpiece about a genius,’ declares the actress Helen Mirren. ‘Splendid beyond words,’ chips in the travel writer Bill Bryson.

Every biography really contains three biographies: one of its subject, another of its author and a third of itself. In this instance, the second is hinted at in these glamorous dust-jacket credits, which must have been easier to acquire for a man who was the New Yorker’s chief theatre critic and author of celebrity profiles. The third, though — the life of the book — is a story too.

When Tennessee took ‘the long swim’ in his suite at the Hotel Elysée in New York in 1983, overdosing on prescription drugs before choking, apparently, on the bottle cap, he had already anointed a biographer: Lyle Leverich, a San Francisco theatre producer who, as Lahr sniffily notes, ‘had never written a book’. His book was a long time coming. Its progress was hampered, and nearly halted, by Williams’s self-appointed literary executor Maria St Just, a woman so keen to pamper the writer’s posthumous reputation that she nearly suffocated it entirely.

When it staggered, wheezing, into print in 1995, Tom: The Unknown Tennessee Williams met with acclaim. Its author may have been a ‘tyro’ (the slight again is Lahr’s) but he was no zero. Yet it only took the tale up to 1944, the year its subject became famous. Leverich died before he could complete the second volume, and the baton passed to Lahr.

What’s odd is that the old pro, whose father Bert played the Cowardly Lion in The Wizard of Oz, presents his book as a ‘stand-alone biography’. No, what he actually says is his publishers ‘have chosen’ to publish it as such, for the ‘stylistic reason’ that the tome, which took him 12 years to write, touches on Williams’s childhood. So the fact that it would be likely to sell more copies as a result played no part in these calculations? The reason this matters is because, as a ‘stand-alone biography’, the book is confused and unbalanced. It’s a Blanche Dubois of a book. Yet as the second volume of a two-book project, which is how it was written, it’s a Stanley to its predecessor’s Stella.

It kicks off on the opening night of Menagerie, which was an early fulcrum of the playwright’s life. You then expect it to rewind to the childhood growing up in St Louis, the precocious school days, the first fumblings with members of the opposite sex, which for Williams were additionally agonising because he was gay. Yet we don’t get this: not really or not much. Worse, there’s almost nothing on the nervous breakdown he suffered in his twenties, which haunted him, and his plays, for the rest of his life. And the reason for this is because the material has been extensively covered by Leverich.

Instead, we get detailed descriptions, which may not be for everyone, of the playwright’s couplings after he came sidling or sliding out of the closet in his thirties. (He used brilliantine, we hear, and not just to keep his hair in order.) And we get close considerations of the plays, of the ways the plot lines plait and link with his private life, which are welcome, and very well done.

Our author can coin a phrase. Williams’s mother Edwina wasn’t just talkative, she was ‘a narrative event’. There are some choice anecdotes: a wonderful one in which the 23-year- old Marlon Brando turns up at the playwright’s home to audition for Streetcar, only to find the lights fused and the floor flooded, so he spends the first hour fixing the lights and unblocking the pipes. Then he picks up his script and begins. ‘Get Kazan on the phone!’ one listener yells, ten minutes in. ‘This is the greatest reading I’ve ever heard!’

One of the best things here is the account of the friendship, more lively on the page than any of the playwright’s love affairs, between Williams and Elia Kazan. The hotly heterosexual director matched pragmatism and clout to Williams’s shimmering poetry. Yet they fell out over changes that Williams claimed Kazan forced on his plays, which were contrary to his artistic vision. This was hogwash, as Lahr brilliantly shows.

The place where art and money meet is a hall of mirrors, with distorted surfaces that make the tall look short, and the fat thin. And perhaps Lahr, whose book is slimmer than it seems, doesn’t fully explain what was going on here.

It’s pretty clear that Williams was nearly always writing, on one level at least, about his homosexuality. When Tom leaves home to be a writer, that isn’t the only reason he leaves. The penchant of Shannon and Blanche for underage partners is an equivalent sexual taboo that, in those days, could be broached. Why, really, won’t Brick sleep with the yearning Maggie?

That’s the reason Williams sabotaged the friendship of a lifetime — and, in the process, his own career — when edits were made to his plays that seemed to suppress further the theme he was already ashamed of suppressing. It reached a crux in the stage version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, which Kazan concluded with Brick going to bed with Maggie, instead of spurning her again, as the author had originally intended.

The ‘false’ ending was retained for the 1958 film, for which Williams was paid handsomely. The funny thing is that, because it starred Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor, who were then arguably the two hottest people on the planet, it was cinematically implausible that they wouldn’t want to sleep together. So as it turned out, the ending worked a treat.