The premise of Richard Holmes’s new book is that there are two versions of Tennyson and one of them is far more interesting than the other. The later one is the bearded bard beloved of Queen Victoria, the patriotic patriarch, who in later life liked nothing better than to read aloud the entirety of his long poem Maud to a large audience, only occasionally breaking off to murmur to himself, “Yes, that is good!” I guess you could call this version Lawn Tennyson.

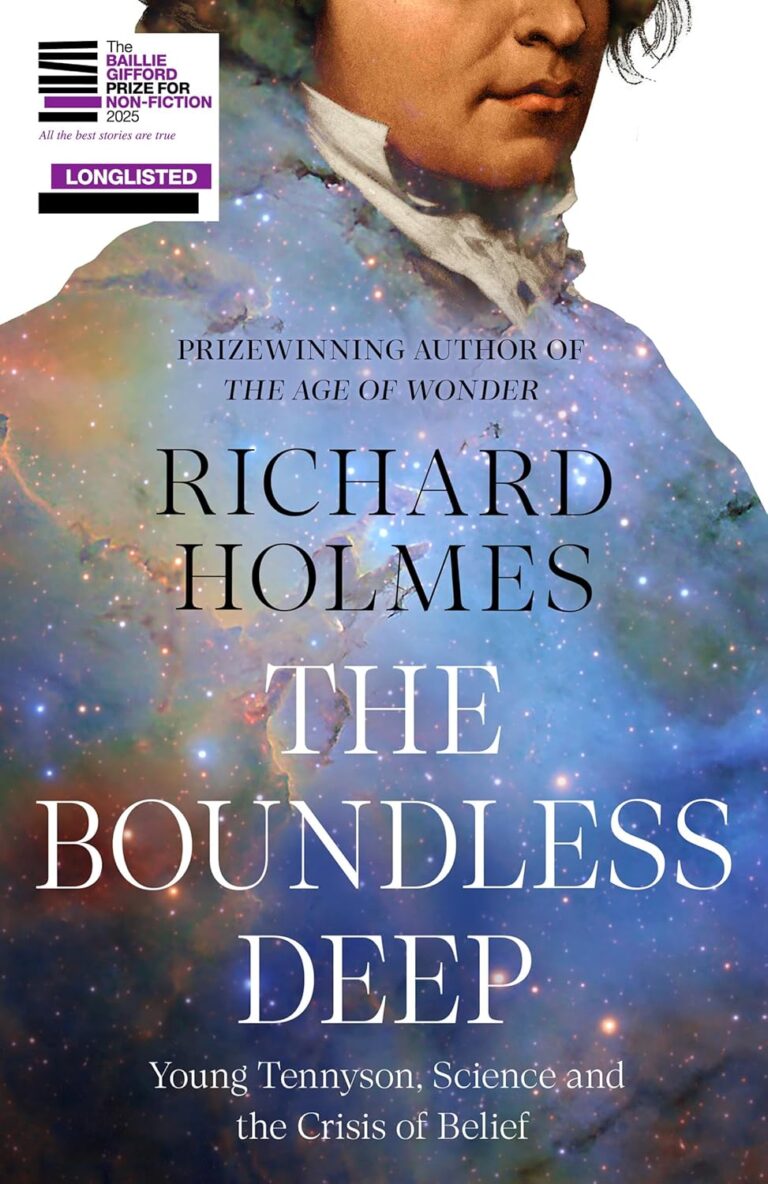

Then there’s the earlier version, the younger one, who I would refer to as Real Tennyson. Before he grew the beard, the poet cut a dash. True, he was a bit of an odd fish, reeking of tobacco, awkward socially, and never the smoothest of suitors. His first words to his future wife, Emily, when he caught sight of her, were, “Are you a dryad or an oread, wandering here?” Yet he was tall, physically strong, and strikingly handsome, with a leonine wave of hair, to judge from the superb portrait of him by Samuel Laurence, done when he was in his early 30s. And of course, he had his phenomenal facility, unmatched in any age, for the musicality of the English language.

Real Tennyson is the subject of Holmes’s excellent biographical study, which begins with his childhood growing up in rural Lincolnshire under the shadow of an abusive alcoholic father, and his precocious years at Cambridge. Holmes puckishly relates the unexpected rising of the behemoth in his undergraduate poem “The Kraken” to the moment in Jaws when we see the shark up close for the first time. This poet, it was clear, was going to need a bigger readership.

The way he finally found it forms the climax of this book. In his twenties, his best friend Arthur Hallam died of a stroke. Tennyson poured his grief into a cycle of 133 sombre, searingly honest poems, which he worked on in secret for 17 years. Some of his friends thought he was being lazy, until they broke the surface in 1850 when he was 41. In spite of the determinedly uncatchy title—In Memoriam A.H.H. Obit MDCCCXXXIII—the volume proved a publishing sensation.

The Boundless Deep works best in its account of the charisma and quiddity of Real Tennyson, and in Holmes’s sure literary criticism, which excels in its adjectives. He dubs the aforementioned title “marmoreal”. One ringing phrase he calls “heraldic”. He praises the “conversational” stanzas of Philip Larkin—this in an intriguing passage, where he notes the loss of metrical skill in modern poetry, to the point where he wonders if, today, we can even really hear Tennyson.

The book is less convincing in its organising theme, which is Tennyson’s engagement with science. In a sense, this is an inversion of the theme of Holmes’s earlier book, The Age of Wonder, which presented figures such as William Herschel and Humphry Davy as the scientific counterparts of the Romantic poets, many of whom were their friends. The Boundless Deep presents Tennyson (the last of the great Romantics), as, if not a scientist, someone who was interested in science, and thought and wrote about it, and had a couple of friends who were scientists. But how uncommon was this?

The best exhibit is a few stanzas of In Memoriam—central ones, it must be admitted, in his greatest work—where the author’s grief takes on a planetary scope, as he bleakly considers how nature cares more for species than individuals, and whether our species will itself ultimately end, as others have before: both notions presented in works of popular science.

Nevertheless, I was left wanting to know more. Tennyson was friends with John Tyndall, the Royal Institution professor, who worked out why the sky is blue. Ditto William Whewell, his tutor at Cambridge, who coined the word “scientist”. What did he learn from Whewell? What did he talk about with Tyndall? And how is science a better prism through which to understand the poet than the theme of love, say, or empire?

In Memoriam is rife with scepticism and existential doubt. That’s what makes it great. Yet as publication day approached, Tennyson lost his nerve and penned a Prologue that affirmed his faith in God and rejected all the question marks to come. A month after it appeared, he married. By the end of the year, he was Laureate. It was his transition from the aesthetic stage of his life to the ethical one. He went from being a private to a public poet. He went from being Real Tennyson to being Lawn Tennyson.