The more I read, the less I seem to know; and the less, moreover, the scientific establishment seems to know about matters one might have thought had been sorted out years ago. Neurologists, however brilliant, still lack a clear understanding of the workings of the human brain, while the purpose served by dreaming continues to elude the investigations of even the most focused of hypnologists. Breasts are another example. Men have invented a thousand names for them, but no one has yet come up with a definitive answer to the question of what, exactly, they are for.

A woman’s milk fountains—or ‘dairies’, as they have sometimes also been known—of course contain her mammary glands, which produce milk for the nourishment of young, but it will be noticed that our primate cousins sport sandbags considerably smaller than our own. Why, then, the special build-up of subcutaneous fat that forms the distinctive cannonballs of the human female? Theories abound. As well as those at the more conservative end of the spectrum, there has been that of Elaine Morgan, who, in the early 1970s, argued that angel cakes were evidence of an aquatic phase in our evolution. According to her, the young would cling to the mother’s kettledrums in the water. She speculated that they might also have served as primitive flotation devices. In The Naked Ape, Desmond Morris suggested that after we learnt to walk on two feet the effectiveness of the buttocks as a sexual symbol was reduced and the female of the species had consequently to develop some sort of frontal buttocks to make up for the loss. Hence her Hindenburgs.

Who knows? Well, not Michael Sims, clearly, who in Adam’s Navel, his lively, populist tour of the human body, tells us what scientists think and writers have said, but not what he himself believes. That perhaps is out of his orbit but a dash of common sense wouldn’t have gone amiss, and not only in the matter of a woman’s flotation devices. There is a place for mentioning the films of Cecil B. De Mille in a cultural history but it’s a small one. Sims himself refers to Samson and Delilah as ‘howlingly campy pseudo-biblical fare’. Why then does he devote more space to it in his chapter on hair than he does to the version of the Samson story told in The Bible, which has clearly had more cultural resonance, even in recent times?

The same chapter includes an interesting discussion of the Nazirite sect, of which Samson was a member (along with Samuel and John the Baptist); the author makes a connection between the Samson story and the treatment in the late 1960s of Jamaican Rastafarians, who had their dreadlocks cut off by the police; he might have enlarged his disquisition by saying how, in his own opinion, hippies fit into the theme

The chapter on navels points out that Adam and Eve may not have had them since they were not born but created by God—a speculation that gave birth to the book’s title. Sims mentions a copper engraving by Albrecht Diirer, in which Adam and Eve do have navels, and an illustration by William Blake in which they don’t, but he doesn’t say which was the more usual in the artistic tradition. The chapter on the eye tells us how often, on average, we blink (once every four seconds), but does not include an explanation of why we cry.

Another annoying thing about this book is that, reading it, one starts to suspect that it could have been written by just about anyone. A surprising proportion does not seem to have required very much research or special knowledge. One might imagine Sims conceiving the idea in the bath, perhaps while he was gazing at his navel, and having half of the book composed in his head before the water went cold.

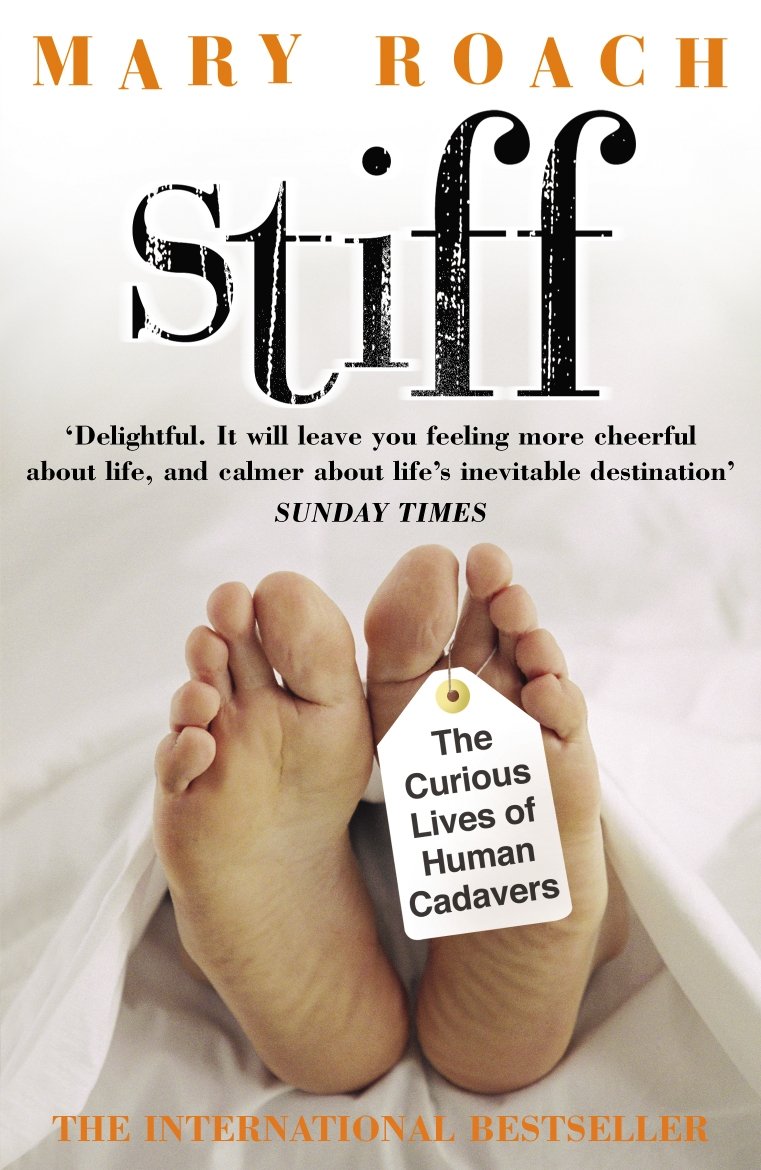

This is not the case with Stiff, Mary Roach’s morbidly fascinating book on the curious things that have happened, and continue to happen, to people’s bodies after they die. Some have been burnt; some buried; some illegally exhumed, in order that they might grace the dissection tables of medical students. Human corpses have been shot (while suspended), to test the stopping power of firearms. They have performed the role of crash-test dummies, to determine what force of impact, for example, an average ribcage can withstand. When a plane crash occurs over water, often the only salvageable evidence is the bodies of the dead, a fact that has given rise to the lugubrious science of injury analysis, whereby bodes are examined for clues to what form the accident took. If chemical burns are evident mainly on the corpse’s back, for example, this suggests it was damaged after the accident, by fire burning on the water. If the body is missing some of its clothing it is likely it was torn off on impact (indicating to the injury analyst that the person and the plane parted company before, not after, the plane hit the water). Even after falling just 250 feet, we learn, ‘typically the shoes get blown off, the crotch gets blown out of the pants, one or both of the rear pockets are gone’. To prove this in the 1950s, a certain Sir Harold E. Whittingham, director of medical services for BOAC, had the Royal Aircraft Establishment take up a gang of fully clothed mannequins to cruising altitude, then drop them in the sea.

These sorts of test continue. At the University of Tennessee Medical Center, for example, there is a special grove dedicated to the study of human decomposition. Since the purpose is primarily to aid homicide investigations by helping to determine the time of death, the bodies have been subjected to various treatments ranging from encasement in concrete to being locked in car boots. Some simply lie out in the open: these afford the author the opportunity during her visit to see for herself the basic stages of decay.

Often the parts of a factual book that consist of personal reportage come across as filling; not here. Roach’s sharply observed, often wryly funny accounts complement the passages of historical exposition, and make bearable the gruesomeness of what she is describing. The way she tells it, there is a constant battle going on between her interest in the subject and her gut-level squeamishness. On being told that, in the process of bloating, the penis and testicles can become formidably large, she wants to know how large.

Stiff is engaging and original throughout, even if it is, in places, a little hard to stomach.