Why do people talk about ‘experimenting’ with drugs when mostly they just mean that they’re doing them? Perhaps, as I write this, I should experiment with a glass of beer.

In any case, one day back in the 1970s — when rock stars were particularly prone to experimentation — Bob Dylan dropped in on Neil Young, who played him a song detailing his extensive drug-related experiments (with grass, cocaine and amphetamines). At the end of the performance, Dylan remarked drily, ‘That’s honest.’

Young still laughs when he remembers this. Partly it was because Dylan, who had done some experimenting himself back in the day, knew where Young was coming from. Also, though, what makes it funny is that all artists are in the business of revelation. All expression, on some level, is self-expression. Yet most take some care about how much they reveal.

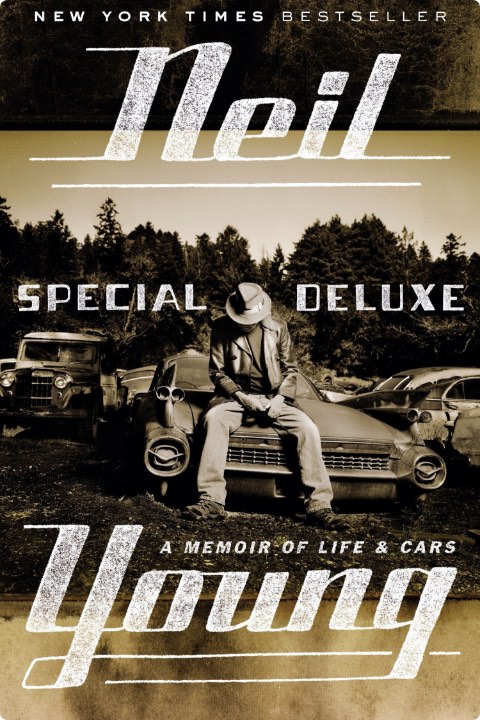

Which brings us to Special Deluxe, Young’s second volume of memoirs, in which the weathered rocker reveals almost nothing about himself over the course of 384 pages. Is that honest? Is it even fair? He’d say yes, since this isn’t really a memoir but, he insists, ‘a book about cars’: specifically the impressive number of classic automobiles he has owned over the decades.

Yet if Young were really fair and honest, he’d have to admit that no one would buy Special Deluxe if it hadn’t been written by the man who gave us songs such as ‘A Man Needs a Maid’ and ‘Like a Hurricane’. The guy with the high whine of a voice, like a cross between a thin mosquito and his own electric guitar, which he can torment, against a pile-up of feedback, into siren wails. (Listening to ‘Cowgirl in the Sand’ recently, while leaving a shop, I was convinced I’d triggered the security alarm.)

To be fair, there are occasional moments of self-revelation, particularly in the first section, in which Young reflects on his childhood in Canada. His parents’ marriage was fractious, which made him an anxious kid. His father hit his mother during a row. A few pages later, he describes the time, aged 11, he was in the backyard struggling to learn the ukelele, when his dad came out and showed him how. He hadn’t even known he could play, and never saw him play again. Later, his parents divorced and Young recalls his mother sitting in the driveway in tears, smashing her records on the concrete one by one.

The author doesn’t ponder it, but the link between music and the trauma of his parents’ break-up is there in both these stories. So, for him, songs became a way of expressing his feelings, but also of escaping them as he toured with his band (in a souped-up hearse, dubbed ‘Mort’). To sustain the evasion, he always had to have wheels.

To be honest, at first I thought all the stuff about cars was a joke. On the brink of intimacy, the author forever pulls back. We turn the page to find yet another of his childish, charming drawings of cars he’s driven and lived in. It’s like a blast of harmonica in a song, which always seems to me a wry admission by the musician that words have, for the time being, failed him.

Then I remembered that cars mean more to those on the other side of the Atlantic. They represent Freedom, and are intricately linked to the ageing American Dream. The dream has been self-defeating. CO2 emissions have poisoned the air it breathed, just as bursts of exhaust from Young’s automobiles cloud his book’s pages. The car-clamour culminates in his adventures bringing the gospel of environmentalism to the masses; or, importantly if impotently, to the ears of politicians, whose pockets are already stuffed with corporate greenbacks.

It is, at the same time, another evasion tactic. This rocker is no writer, his prose style so determinedly bland in places that you wonder (again) if he might be joking. William Blake was a ‘great poet’, he informs us; Canada is a ‘beautiful country’. The simplicity can be effective, but sometimes it’s a little naff — as when, for example, he refers to his cars as living creatures.

Towards the end, he details his travels in a remodelled 1959 Lincoln Continental, named Miss Pegi, after his wife of 36 years. At one point, he confesses, ‘I was starting to have a relationship with Miss Pegi.’ Yet the truth, to judge from recent media reports, is that he was falling in love not with his car but with the actress and environmentalist Daryl Hannah.

Only once does Young hint at his marital problems. Then he concludes, ‘I guess you might say that I don’t want to talk about it.’ Now that, to be fair, sounds pretty honest.