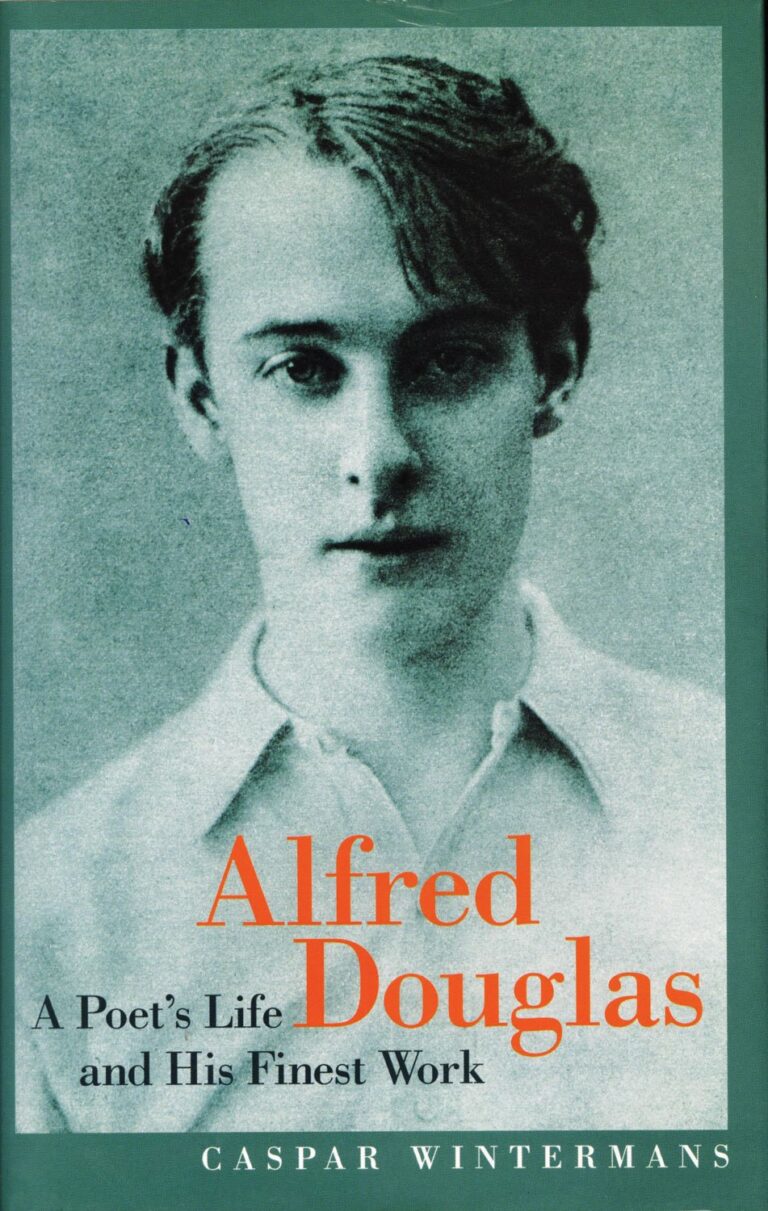

You can learn everything you need to know about Alfred Douglas by reading a decent biography of Oscar Wilde. Well, almost everything. From a glance at the photographs in Richard Ellmann’s book, for example, you can see that Douglas, in his twenties, had a kind of boyish, petulant prettiness. (It still isn’t immediately obvious to me what it was about his physical appearance that the playwright found quite so appealing. Is it possible the young Lord Alfred was at his most attractive with his clothes off?) Other, and weightier, minds than Caspar Wintermans’ have provided accounts of the first fatal meeting in 1891 between Wilde, then thirty-seven, and Douglas, still an undergraduate; of their subsequent passionate affair; and of how Wilde got dragged into the even more passionate feud that raged between Douglas and his whip-wielding, half-mad father, the Marquess of Queensberry, which was to lead to the playwright’s incarceration and, ultimately, death in 1900. Douglas lived on for another forty-five years. The question is: was there anything he did, or suffered, during that time which merits serious attention?

Wintermans’ answer is evidently yes. This book is neither the first homage he has paid to his lordship—he made a documentary, Two Loves, about him in 1999, and edited his wife’s diaries in 2005—nor the most recent. It turns out that the work under review is a translation, by the author himself, of a biography he published in Amsterdam eight years ago, entitled De boezemvriend van Oscar Wilde. The author’s English is excellent, as second languages go. However, I can’t help wondering if, in his native tongue, he was more successful in controlling the fruitiness of his prose. Either way, we are pretty sure in what kind of biographer’s hands we find ourselves, when the sentence opening the passage on the subject’s university years consists of the single word: ‘Oxford!’ Similarly, I was struck—and, despite myself, rather charmed—by the way Wintermans, after quoting Oscar’s words to ‘Bosie’ a few days before he was sentenced (‘What wisdom is to the philosopher, what God is to his saint, you are to me’), observes simply: ‘Holy ground.’ Single-sentence paragraph. End of Chapter One.

Stylistic matters aside, the defence of Douglas offered by his biographer is, first, that he has been unjustly dealt with by Wilde-worshippers over the decades. This is probably valid—the temptation to cast Wilde as a gentle Aesthetic giant, betrayed by his poisonous pupil, has been too strong for some to resist. Nevertheless, the injustice has perhaps not been as great as Wintermans claims. His second point is that Douglas is a ‘first-rate poet’, worthy of consideration in his own right. I’m not so sure about that. Douglas had an ear for fine-sounding phrases, true, and he rarely wrote a bad poem—but on the other hand, he wrote remarkably few over the course of his life, as is demonstrated by the way Wintermans manages to fit most of them into the back of this book, along with his copious notes (the biography itself, which proceeds at breakneck speed, occupies a mere 170 pages). Moreover, in several cases, Douglas’s staid, stately verse seems to ask to be assessed in the context of the affair for which he is remembered. In ‘The Dead Poet’, for example (a sonnet composed in ‘Paris, 1900–1901’), he describes having a premonition of the death of a great writer, whose ‘golden voice’ could ‘conjure wonder out of emptiness’. No prizes for guessing who he’s referring to. And when Douglas, like Wilde, ended up in gaol (for libelling Winston Churchill), he, like Wilde, decided to pass the time writing about the experience. Wilde had called his work De Profundis. So what did Douglas choose as the title for his sonnet-sequence inspired by prison life? In Excelsis—a kind of snide riposte, surely, to Wilde’s mellifluous apologia.

The six-month term Douglas served in Wormwood Scrubs in 1924 was the low point of his life. His wife, and his looks, had left him. The various magazines he had worked for had either folded or found someone else to edit them. He had disowned his son, converted to Roman Catholicism, and become a rabid moral conservative and law-suit addict. It may be the case, as Wilde said, that all women grow up like their mothers, but Douglas was in serious danger of turning into his father. The most unexpected pleasure provided by this unusual biography is the sketch it gives of its subject’s final years, as—to everyone’s surprise—he mellowed into a curiously detached, avuncular figure, befriended by the likes of John Betjeman and Wyndham Lewis. The former described Douglas as ‘a vastly entertaining man who gave one a sense of holiday and exaltation whenever one was in his company’; the latter remembered that nothing made the once irascible nobleman lose his cool, ‘except the poetry of Mr T.S. Eliot’. Once you have learned that his wife, with whom he had been reconciled, predeceased him by a year, that his son fell prey to schizophrenia, and that Douglas himself died peacefully in his sleep on the morning of 20 March 1945, you really do know more or less everything you need to about the life of Oscar Wilde’s lover, post-Wilde. That said, you might be interested to have a quick look at ‘The Dead Poet’. It isn’t at all bad.