I received an email from Tom Hodgkinson the other day. ‘Dear Tom Hodgkinson’, it began, before going on to make a polite request that I didn’t write any more articles under the name ‘Tom Hodgkinson’, and signing off with the words, ‘Yours etc, Tom Hodgkinson’. I had just written a piece in The Guardian about a marathon I’d done, which had been accompanied by various (posed) photographs of me in tight shorts, and infused generally with a spirit of neo-Fascistic body-worship. My namesake, who also writes for The Guardian, was protecting his reputation.

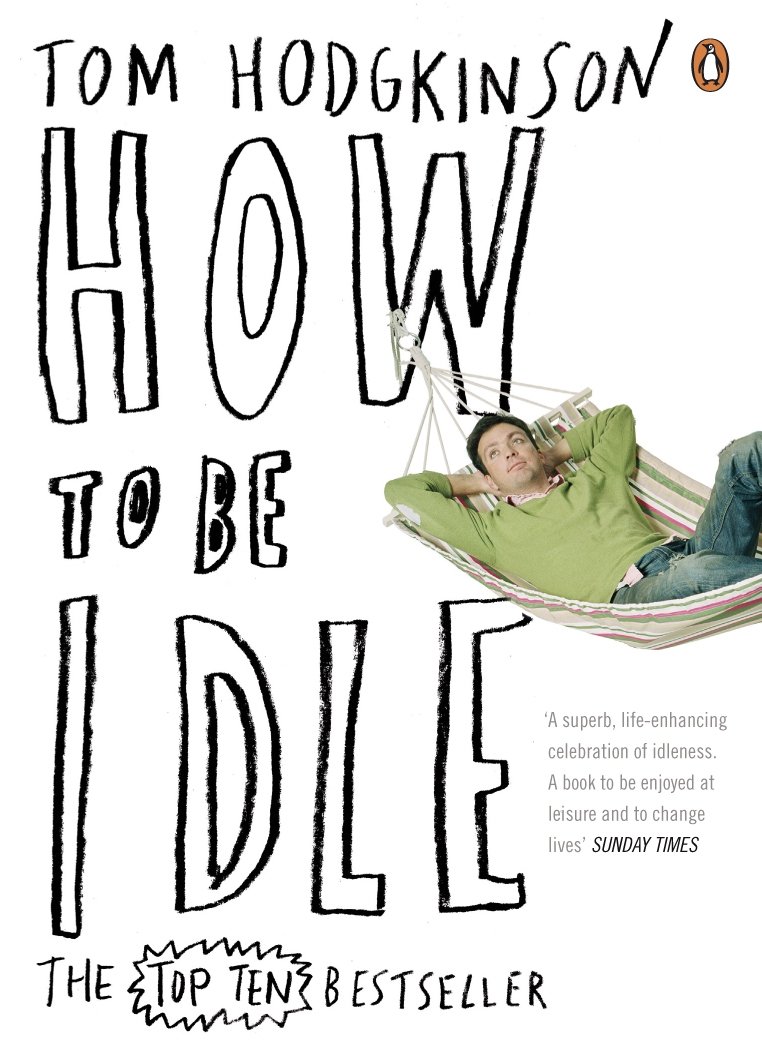

Editor for the last ten years of The Idler (a biannual magazine devoted to ‘alternative ways of living’), Tom Hodgkinson is not interested in exercise, preferring instead the pleasures of loafing, shirking, and skiving. He’s a scrimshanker, in other words, and How To Be Idle is his manifesto. Arranged in twenty-four chapters, it devotes one to each hour of the day, and the author’s recommendation of how best to waste it.

The book includes passages on sleep, sex, tea-drinking, drug-taking, drinking, and—one of my personal favourites—how to handle a hangover. According to Hodgkinson, the key to coping with the last of these is not to do anything that you do not actively want to do. Released from the burden of duty, the mind is free to enjoy the hangover for its virtues: the way, for example, it enables the eye to invest objects with ‘an incredible, luminous significance’. His friend Josh Glenn develops the idea. To his way of thinking, ‘the hung-over eye, which is somehow between the appraising eye of the teetotaller and the foggy eye of the drunkard, may be the model for Hinduism’s “third eye” of enlightenment’. He was presumably hung over when this thought occurred to him.

Enlightenment, or the quest for it, is a common theme here, and behind the jokes, quotes and anecdotes that lace Hodgkinson’s fittingly effortless prose lurks the seriousness of an evangelist. His message is: it’s the workers, not the shirkers, who are asleep. As Aristotle said, ‘The object of work is leisure’ (one of the few encapsulations of the idler’s spirit not cited in this book), and yet that is what so many in the capitalist West seem to forget. Some of the 24/7ers who labour in the money markets may, perhaps, be said to take the cut and thrust of finance as their raison d’étre. As for the rest, the question remains: what on earth do they think they’re doing?

Against the Protestant work ethic Hodgkinson balances, in turn, the philosophy of Izaak Walton, under whose representation in Winchester Cathedral’s stained glass the inscription reads, ‘Study to be quiet’; the wisdom of Pascal, who ascribed all man’s unhappiness to his inability ‘to sit quietly in a room’: and, as an articulation of alternatives to work. some lines from the wonderful sixteenth-century poem ‘Proper Moments For Drinking Tea’ by Hsii Ts’eshu:

Engaged in conversation deep at night.

Before a bright window and a clean desk.

With charming friends and slender concubines.

Most people these days don’t have time for conversations deep at night, let alone slender concubines. Tea meanwhile—to which I am a recent convert—is scorned in favour of coffee, which sets the heart racing and the nerves a-jangle.

This book isn’t perfect. It couldn’t be said to have any real intellectual rigour (perhaps that would have been self-defeating). I would have liked more exploration of the distinction between work and occupation. Work, Hodgkinson tells us, is anything you have to do, but what if what you have to do is also what you want to do? I would have liked to know what the author thought of total idleness, the sort of complete immobility that might grip someone in the throes of an existential crisis. As a fan of dancing, drug-taking and messy, shameless sex, he clearly isn’t prejudiced against activity per se. I would have liked, too, to learn how Hodgkinson freed himself from the chains of the nine-to-five. Did he come into an inheritance? Does his girlfriend take the brunt of his financial obligations? Or is he such a brilliant freelancer that he makes his living from that alone? My personal suspicion is that he must be an expert household economist. But again, I could have done with a few pointers.

Nevertheless, in his life and in this book the author is 100 per cent on the side of the angels. Idling is something he believes in and he practices what he preaches. I replied to his email with, I thought, a fair amount of good humour, saying that I for my part did not wish to be associated with him, as it might be bad for my reputation, and then promising to style myself as ‘Thomas’ from henceforth. My tone was pleasant and friendly. I’d have thought he might have responded, at least with a ‘thanks’; but he never did. He was too busy being idle.