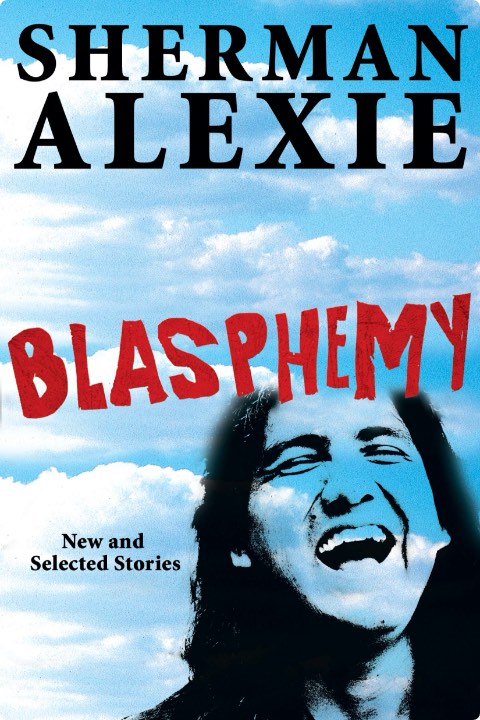

A 465-page volume of short stories by a Native American author — it’s not, perhaps, the kind of thing everyone would automatically reach for, if they hadn’t already heard about it. Well, now you’ve heard about it, so you don’t have that excuse. Reach for it. Read it. Because the stories it contains (15 new, 16 old) are moving and hilarious, and they amount to an education.

Take the term Native American, for example. Isn’t this the accepted way to refer to the author’s ethnicity? You’d have thought. Yet Sherman Alexie avoids it, referring to himself and his characters as ‘Indian’. Everything he writes is imbued with a consciousness of the irreversible wrong visited on his ancestors, but this is as often wry as plaintive. The knock-on consequences include alcoholism, which isn’t funny, and a tendency to perform traditional songs and dances, which can be very silly indeed. Just occasionally, Alexie gets sentimental with his aboriginal schtick (see, for instance, the ending of the first story here, ‘Cry Cry Cry’), and then I was reminded of that scene in The Last of the Mohicanswhen a long-haired Daniel Day-Lewis murmured about the sun drawing forth from his mother’s breast the stars, etc etc, while a sultry Madeleine Stowe swooned, and the rest of us winced or tittered.

On the whole, though, this is exactly the kind of thing Alexie likes to poke fun at. In ‘This Is What It Means To Say Phoenix, Arizona’, one Indian meets another in a store and consoles him on the death of his father. How did you hear about it, the second man asks. To which the first replies: ‘I heard it from the birds. I felt it in the sunlight. Also, your mother was just in here crying.’ It’s not surprising to learn that Alexie does stand-up, since his humour often, as here, has the rhythm of a routine. At other times, it comes from a wiser place, some flashpoint of truth.

‘If you really want a woman to love you, then you have to dance. And if you don’t want to dance, then you’re going to have to work extra hard to make a woman love you forever, and you will always run the risk that she will leave you at any second for a man who knows how to tango.’ This, from the excellent longer piece ‘War Dances’, made me laugh, then made me think, and finally confirmed my resolution never to visit South America.

The weakest stories here are the shortest, like the two-page ‘Breakfast’ (the dead father theme again), and the three-page ‘Fame’ (a guy is rejected by a girl for being fat). Non-events both.

The strongest are the longest, which find room to go from serious to funny and back again, without recourse to cheap tricks. In ‘Do You Know Where I Am?’ a guy tells a small, unnecessary lie and his girlfriend leaves him. Later she forgives him and they marry, and a decade afterwards she has an affair, which she confesses to her husband. You can ask me three questions, she says, and then I never want to talk about it again. Devastated, for his third question he asks her what she and her lover did; which is to say, where did the other guy put it? Wordlessly the wife points to three places. Yup, three. There’s a pause. Then they both start to laugh. They laugh so hard they roll around on the floor. The tale isn’t a fantasy; it goes on to explain that it’s only after two years that the marriage really recovers.

I have a sordid confession to make when it comes to fiction. I only really like to read stuff that seems somehow about me. (I was disappointed by The Hobbit, let me tell you.) I realise this makes me a bad reader, not to mention reviewer. But what I want to know is: how am I made to feel as if Alexie’s book is about me too? Is it, perhaps, because we all find ways to believe we’re part of some oppressed minority, whether it’s ethnic, sexual, or merely that we’re well-educated, well-off and white (howl)? Perhaps. But I think it’s also testament to Alexie’s gifts that he can write 31 stories about the experience of Indians in present-day America, and do it in such a tone of relevance.