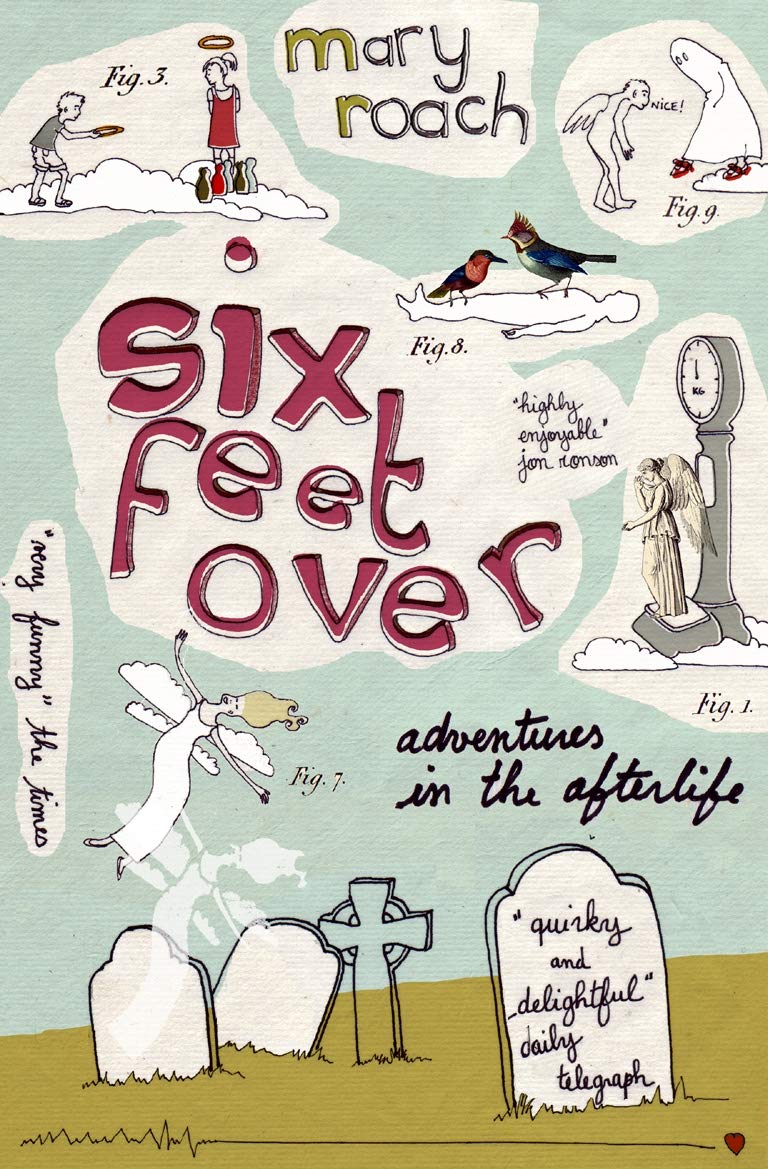

What happens to us when we die? Is that the end, the final curtain? Or does some essential part of us survive? Do our souls, in other words, live on? Of course they bloody don’t, is Mary Roach’s firm conviction at the start of this sassy, egocentric exploration of the “afterlife”—which takes us on a Cook’s tour of mankind’s struggle to believe in some kind of life after death, with diversions including a brief history of preformationism (the idea that each sperm contains a tiny, fully formed human being), a great deal of ectoplasm (the yucky stuff that dribbles from the mouth, nostrils, and occasionally other parts of mediums when they go into a trance), and an account of the bizarre experiment that was conducted in 1901 to discover the weight of the soul (twenty-one grams, if you’re interested).

The book has many highlights. There’s a great throwaway line, for example, in the author’s discussion of the theory of maternal impressions: the belief that a person’s physical irregularities can be traced back to a particular fright suffered by the mother during pregnancy. This, Roach says, was put forward as an explanation for the hideous deformities of one John Merrick, aka the Elephant Man—“as well as those of a lesser-known travelling spectacle, the Turtle Man”. I longed to know more about the Turtle Man. I would have liked, above all, to see a photograph. But there was something magnificent, I felt, about the author’s refusal to give further details. I also enjoyed aspects of her discussion of Hindu beliefs regarding reincarnation. The Ordinances of Manu, a tome of legal code from AD 500, sets out a list of specific karmic punishments for particular human crimes. The man who steals a kitchen utensil, I seem to remember, will be reincarnated as a wasp; or is it that the man who kills a wasp will be reincarnated as a kitchen utensil? The Brahman who has “deserted his own proper rules of right”, meanwhile, will find himself reborn as ‘the ghost Ulkamukha, an eater of vomit’, which sounds like something one might want to avoid.

Vomit-eaters apart, have you ever seen a ghost, or felt as if you had brushed up against a spectral presence? I haven’t, but I was intrigued by one possible explanation for the phenomenon: infrasound. The theory goes that there are certain frequencies of sound that are inaudible to the human ear but which can still have a physical effect on us, such as chilling the blood or making the hair stand on end. In other words, a tumble drier might go into overdrive in the basement—and in the east wing, a weekend guest finds himself developing an unexpected Mohican. Tigers, apparently, employ a type of infrasound to warn off rivals. If you want to experience what this “sounds” like, go to www.acoustics.org/press/145th/Walsh2.htm: “Even though I know what’s coming,” Roach writes, “it scares the rubber dog doo out of me every time I play it.” Let’s leave on one side for a moment the irritating infantilism of her reference to “rubber dog doo”. I went to the website, followed the instructions. It was a disappointing experience—not scary in the least.

To my surprise, however, I found that the worst thing about Six Feet Over was not its author’s judgements but her tone, which was one of smug, journalistic cynicism. A cynic myself, I still shrank from Roach’s cold, clever, US liberal certainties—and was massively turned off by her insistent nostalgie de la boue. The author seems to find something inherently amusing in any reference to excrement, farting, penises or vaginas. It all, alas, kept coming back to the rubber dog doo.

Where was the academic rigour? Where was the discussion of the myth of Er in Plato’s Republic, which sees the heroes from Troy reborn in ways that reveal their characters and desires? (Agamemnon is reincarnated as an eagle; Odysseus, tired of the heroic life, as an ordinary citizen.) I was left wondering how believers in metempsychosis account for population increase. Do souls sometimes divide into two? Six Feet Over fails to provide answers to these important questions. Where was the chapter on regression, by which people under hypnosis appear to slip back into the personalities of their previous incarnations? Why was there no analysis of the evident deep human need to believe in some kind of life after death: the question not of whether people are right to believe it, but of what it says about them, the fact that they do? In my opinion, reincarnation is such a silly idea that it just doesn’t work to approach it, as Roach does, in a spirit of mockery. It’s a bit like shoulder-charging an already open door: an unremarkable achievement, which is likely to end with you falling on your face.