Coleridge got high here. Under the same roof the scientist Sir Humphry Davy fell for his employer’s wife. Yet the estate agent’s description of the grade II* listed Bristol townhouse, close to Clifton, mentions only that the surrounding area became significant owing to the work of “Davy (who lived in this very house)” and that there’s some “useful cellar space”.

Talk about understatement. The vaulted cellar once housed Davy’s kit for making nitrous oxide, also known as laughing gas, which he inhaled in vast quantities as part of a study of the medicinal uses of various gases, many of which had only recently been discovered.

Davy, whose birthday is today, was a small man with boundless energy, an artist as much as a scientist, who by 1798 — at the age of 19 — had written a novel and much of an epic poem about Moses, in the style of Milton. That year he was invited to move from his native Cornwall to Bristol by a doctor named Thomas Beddoes, who needed an assistant for the “pneumatic institute” he was setting up. Davy lived for a few months in Rodney Square with Beddoes and his young wife, Anna, with whom he promptly fell in love. The pair wrote passionate poems to one another. One of Davy’s ran, “Anna, thou art lovely ever, / Lovely in tears, / In tears of sorrow bright, / Brighter still in tears of joy.”

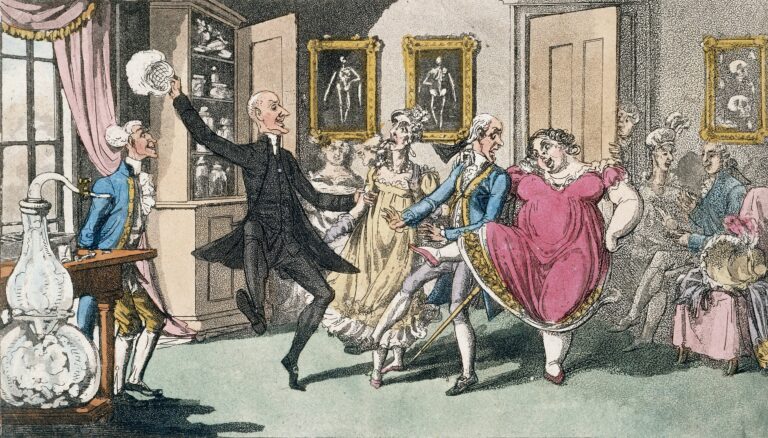

Soon afterwards Davy moved to 6 and 7 Dowry Square, where the Pneumatic Institute was inaugurated. He lived at No 6, all 3,240 sq ft of which is now for sale. In the weeks that followed, the young chemist experimented on himself by inhaling hydrogen, then nitrogen, then a mix of carbon monoxide and hydrogen, then carbon dioxide, then nitric oxide and, finally, nitrous oxide. In every case the result was unpleasant — in a couple of cases near-fatal — with the exception of nitrous oxide, which proved a revelation.

After taking it, Davy exclaimed: “Nothing exists but thoughts.” His friend, the poet Robert Southey, declared that Davy had invented “a new pleasure”. Coleridge himself, who also experimented with laughing gas at 6 Dowry Square, said that he seemed to see things as if “through tears” and compared the experience to entering a warm room out of a snowstorm.

Some have said that Davy’s attempts to write poetry under the influence of nitrous oxide may have inspired Coleridge’s later writings after taking opium, notably Kubla Khan. I also find myself wondering if his nitrous oxide work contributed to the creation of Roget’s Thesaurus. Peter Mark Roget, who worked at the Pneumatic Institute. The latter tried nitrous oxide and complained he couldn’t find words to describe the sensations it produced. All the more reason, then, for him to write his famous compendium of synonyms.

Katy Grant bought the four-bedroom, three-bathroom property, which has a 46ft rear walled garden and use of the communal gardens in the square, with her husband, Chris, in 2018 after they returned with their children from years abroad doing aid work. She was attracted to its humanitarian heritage rather than its scientific legacy, calling it a “privilege” and a “benediction” to live in the property. The Pneumatic Institute was “almost the first iteration of public health for the poor”, she says. On the gas-taking? “At least they had a nice one-minute high.”

Davy hinted at, but never followed up on, the possible uses of nitrous oxide as an anaesthetic. A few decades later it would be adopted by dentists around the world to numb the agony of the drill. Yet for Davy — although his time in Dowry Square may have brought him heartache and left him forever remembering wistfully Anna Beddoes’ “tears of joy” — the episode ended happily. The sober report he wrote on the effects of nitrous oxide (Coleridge didn’t get a mention) caught the attention of the members of the Royal Institution in Mayfair, central London.

They were looking for a new lecturer in chemistry who would be able give talks that would entertain and educate the public. Clearly Davy was their man. He bade farewell to Dowry Square and made his way to London, where he became the toast of the town.

His talks at the Royal Institution were so popular that Albemarle Street was turned into what is believed to be London’s first one-way street, to ease the traffic as ticket holders clamoured for entry. He went on to identify nine elements and save countless lives with his lamp for miners.

It’s quite a story, and you’d scarcely guess it from the simple plaque, partially concealed by a sprig of wisteria, that adorns 6 Dowry Square.