What has been the biggest disappointment of my life? Along with losing my virginity and seeing U2 at Wembley, it was probably when the film Notting Hill came out in 1999.

A romance that isn’t romantic, a comedy with no good jokes, this intolerable follow-up to Richard Curtis’s almost flawless Four Weddings and a Funeral sees Hugh Grant’s cringing bookshop-owner meeting Julia Roberts’s odious actress, spending the night with her before deciding, bewilderingly, that they can’t be together, then changing his mind after she gives him an original Chagall and jumping in a car for a faked-up “rom com run” to tell her that he loves her before she gets on a plane—which presumably, if she had, would only have meant he had to wait until she landed, when he could have given her a call.

Now it turns out that this rotten swizz, this stone-cold Turkey Twizzler of a movie, is still causing people pain a quarter of a century later. This week it was reported that residents in the candy-coloured W11 streets where it was made have had to endure fans of the film, more recently joined by Instagram influencers, thronging the pavements to get pics for their social media feeds. Some have the gall to enter the front gardens to get the right shot. They make a lot of noise. They leave rubbish behind. Locals are so irritated that a number of them have taken the desperate step of painting their homes black.

What enrages me most, though, about this is the evidence it provides that there are still people out there who think Notting Hill is a good film.

Let’s summarise. Curtis scored a surprise hit with Four Weddings by casting Grant as a posh avoidant who panics when he sees all his posh friends getting married, until the death of a slightly older posh friend forces him to get serious. Solid. Relatable. Crammed with good jokes. The screenwriter’s next move was to cast Grant as a posh avoidant with a group of posh friends, including (again) one with a disability and a working class flatmate. Again he’s in love with a glamorous American out of his league.

Jokes are repeated. “Fuckety fuck!” Grant exclaims in the first film. “Shittety brickety,” he mutters, less plausibly, in the second.

The laziness of all this is compounded by the film’s incredibly unconvincing disavowal of privilege, which in fact it would do far better to own. In Four Weddings, Grant’s friend Tom cheerfully admits to being the seventh richest man in England. In Notting Hill, despite the fact that all the characters are obviously loaded, they claim to be poor. Grant’s friend’s restaurant is failing. His own bookshop, located in prime real estate just off Portobello Road, is struggling to stay afloat. Yet he owns a house with a roof terrace in the heart of Notting Hill, which (a glance on Zoopla reveals) would now be worth £3 million.

Need another way to relate to these guys? They’re all total losers, we’re assured. Grant’s sister Honey works in “London’s worst record store”. His friend Max is “the worst cook in the world”. His friend Bernie is “the worst stockbroker in the whole world”. His friend Tony is “the worst restaurateur”. His flatmate Spike is “the stupidest person you’ve ever met”. The film is imbued with a bizarre glorification of uselessness that is epitomised in the notorious “brownie” scene.

Personally I have always struggled to care for a brownie (there’s something twee about the very word), yet here it randomly becomes the prize in the sob story Olympics. One of Grant’s posh friends can’t have children. Roberts has no self-esteem. And so on, and so on. Supposedly a classic, the scene is actually weird and depressing.

Vulnerability is winning. Self-contempt, less so. Given that Americans are supposedly unable to understand our tendency to talk ourselves down, it’s hard to know what Roberts sees in Grant, unless it’s the fact that he’s the only person on the planet who is arguably better-looking than her.

That said, she has some off-putting qualities herself. She’s rude one moment, needy the next. And she has zero dress sense. The teenage crop top she wears in one early scene is a very odd choice. When she sports a man’s tie in the Ritz, it’s meant as a tribute to kooky Diane Keaton in Annie Hall. But it leaves Roberts looking like a pantomime horse.

Speaking of kooky, the entire last scene—the press conference in the Lancaster Room at the Savoy Hotel—is ripped off from 1953’s Roman Holiday. In that much better film, Audrey Hepburn’s celebrity princess reveals her love for a journalist in the crowd with a carefully nuanced answer. In Notting Hill, Roberts does something similar with a less nuanced one.

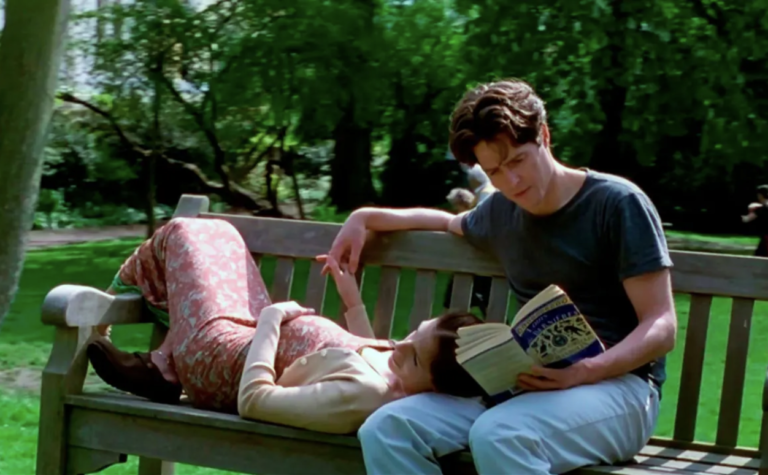

We then cut to a shot of the pair relaxing together in a residents’ garden, reading Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, of all things. Just as Chagall (along with Munch and Dali) is the top-dollar painter for people who don’t like painting, Louis de Berniere’s middle-brow blockbuster is the book for people who don’t read. And Notting Hill is the film for people without eyes.

And Ronan Keating’s When You Say Nothing At All, which plays over one key scene, is the song for people who lack access to any of the five senses.

It’s fashionable to make a noise about how much you hate Curtis’s next big rom com, 2003’s Love, Actually. But as a matter of fact, Love, Actually is very far from being the worst in his rom com oeuvre. It contains one or two good jokes and Emma Thompson’s heartbreaking turn alone makes it worth a watch. Not so Notting Hill.

It’s time we called time on the idea that there’s any merit in this slow, insipid, neighbourhood-wrecking stinker.