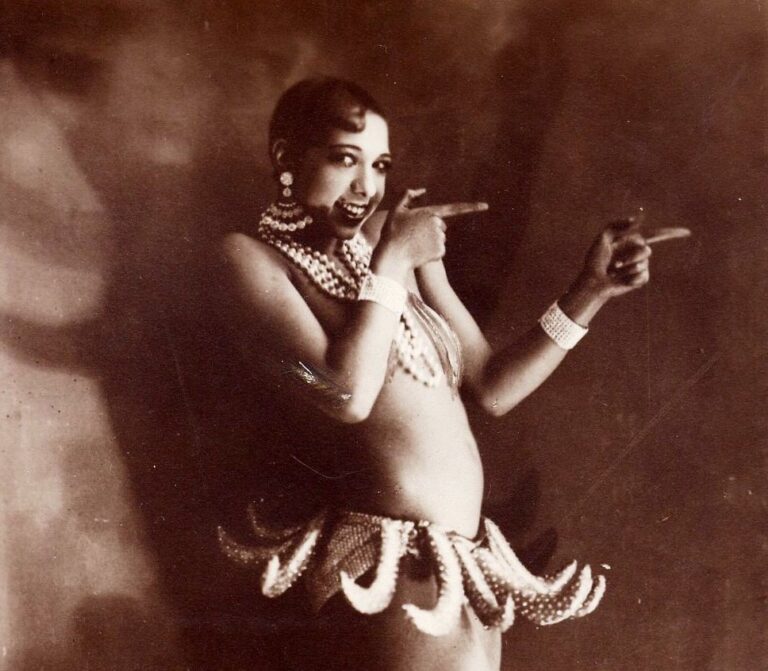

Jean Cocteau. Virgil Thomson. John Cage. Joan Mirò. Josephine Baker. Edgard Varèse. Marcel Duchamp.

Piet Mondrian. Albert Einstein. Hélio Oiticica. Lygia Clark. Fernand Léger.

That’s the complete list of the names I spotted among the wall blurb notes at the otherwise excellent Alexander Calder exhibition, currently showing at London’s Tate Modern. And it poses the question: were the curators concerned that the American sculptor’s mobiles and wire portraits were so insubstantial, they had to bolster his credentials by scattering impressive names?

This kind of cultural name-dropping, of course, is neither new, nor restricted to the art world. Journalism is rife with it. Here are three recent examples.

Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian, reviewing the film Carol: “There is the Nabokovian flourish of a revolver.”

A.A. Gill in The Sunday Times, on the recently screened BBC drama Capital: “[It] suffers from Shavian point-scoring and Hogarthian overstatement.”

And Leo Robson, in the New Statesman, writing about Lee Child’s gritty and hard-bitten hero, Jack Reacher: “The tradition he comes from is not French existentialism but English empiricism, stretched a little to include Darwin and early Wittgenstein.”

Is the room starting to swim? Are you slumped over your laptop, or clinging to the edge of a table for support?

These are not bad writers. On the contrary. It’s just a journalistic trick, like throwing in a joke or personal detail to sustain the reader’s interest. Yet the cultural name-drop is more of a slap. It says: listen up! I carry the authority of knowledge, which is why I’m the one writing and you’re the one reading.

That slap can sting. A sequence of such slaps can induce cultural concussion. My collective term for this syndrome, though, which results from prolonged exposure to intellectual ostentation, is Cultural Name Fatigue, and it was much in evidence at the Tate that day, where many of my fellow visitors had the telltale, cross-eyed look. Some tottered. Others teetered. I saw one elderly lady being helped to a padded bench, where she convalesced horizontally. And I recognised the symptoms immediately, because I used to suffer from them myself.

That was before I hunkered down with a sympathetic friend, and spent a year co-writing a cure for Cultural Name Fatigue. It’s called How to Sound Cultured: Master the 250 Names That Intellectuals Love to Drop into Conversation and it’s devoted to the names that used to give us both that crazed or cross-eyed look. Our aim isn’t highfalutin. It’s to de-frighten the frighteners: to parry their slap and draw their sting.

In pursuit of this, we resorted to every possible tactic. Trivia, for one. Did you know, for instance, the name of the only winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature to have an entry in Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack? The answer is the playwright Samuel Beckett, who played two games for Dublin University against Northamptonshire as a left-arm medium-pace bowler (but failed to take a wicket).

Or were you aware that the reason T S Eliot included the middle initial in his name is because, otherwise, it would have spelt “toilet” backwards?

Sex inevitably looms large. (Have you noticed that about sex?) The mono-browed Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, we discovered, reacted to the news that her husband had betrayed her – with her own sister – by having an affair with the exiled Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky. Which, as responses to infidelity go, is actually pretty hard to beat.

Equally, I was thrilled to learn that, according to one of Saul Bellow’s mistresses, the great novelist “didn’t know a clitoris from a kneecap”. Was he the only example of a Nobel Laureate of whom this could be said? Who knows?

I couldn’t help wondering if the woman’s claim were literally true. And if so, what Bellow’s views were on above- versus below-the-knee hemlines.

This is tittle-tattle, and we make no apology for it (neither for the tittle nor for the tattle). However, we’re happy to make a reasonably robust defence.

Anti-intellectualism has a fine and healthy history in this country, but sometimes it’s just a knee-jerk reaction (or as Saul Bellow might have put it, a slip of the knee). Incredibly, How to Sound Cultured – a book whose cover features a picture of a dog wearing sunglasses – has been accused of elitism on the Radio 4 Today programme. Tragically, I was too hungover on the morning in question to do much more than gawp and drool. Yet now, after weeks of brooding, I can offer my considered response: that’s nuts. But it tells you something about the extremity of the two sides in this debate.

On one side, you have the cultural name-droppers,whose allusions are often a little unnecessary (in the aforementioned quote, not much is lost if you delete the words “Shavian” and “Hogarthian”). On the other side, you have those who reject the game, who say that a book containing information about the likes of Cocteau and Duchamp is intolerably pretentious, even if it does have a dog on its cover.

Naturally we disagree. We reject the automatic veneration given by some, especially on the continent, to many of these characters.

Equally, ignorance can never be the answer. You should know a little bit about these names. Then, if you’re interested, you can find out more.

This is always a problem for anyone who likes biographies. How do you avoid committing yourself to 500-plus pages on Arthur Schopenhauer, say, only to discover that actually you’re not that interested in the misogynistic father of existentialism?

Our book, which is available from all good bookshops (but not from the bad ones), contains 250 fizzing miniature biographies of everybody from Schopenhauer to Shakespeare, none of which will take up more than a few minutes of your time. Now is that good value, or what?

But I feel, now that I think about it, I may have given Schopenhauer a bad rap. It’s true he had issues with women, but so would you, if you’d had his mother. And he loved dogs, keeping a succession of pampered poodles, to each of which he gave the identical name Atma (the Hindu word for the universal soul).

The discovery that they were pet-lovers was one way in, we found, to the humanity of some of our names. The novelist Ernest Hemingway, for example, was famously a cat man. As was William S. Burroughs. Then again, the latter also accidentally killed his wife while drunkenly attempting to shoot a gin bottle off her head. He later had the gall to say that the experience had made him as a writer. So you might want to think twice, before warming to Burroughs.

Some cultural titans have had far more outré tastes in the pet department. As an undergraduate, the poet Lord Byron kept a bear in his rooms at Cambridge. (In his defence, he pointed out that dogs were forbidden.) But the prize goes to the Danish scientist Tycho Brahe, who befriended a fully grown moose. Having said that, he can’t have loved the moose all that much, since he ultimately killed it after challenging it to a drinking contest, which proved too much for the animal.

Sex, pets and drinking: three of the great humanisers. A fourth is the presence of a dissatisfied wife. There’s the story of how James Joyce and his wife Nora were once visited by a publisher in Paris, who at a certain point in the evening took it upon himself to inform Mrs Joyce that her husband was a genius. “You don’t have to live with the bloody fool,” she replied.

Or I also like the one about Marcel Duchamp, who more or less gave up creating artworks in order to devote himself to playing chess, which he did obsessively. Eventually his wife Lydie grew so exasperated that she glued his chess pieces to the board.

Sadly for her, Duchamp wasn’t so easily deterred. He went on to play a famous chess game against the experimental composer, John Cage. They rigged the board up so that each time one of them moved a piece, it would trigger a note of music. Thus, as they played, they composed a symphony.

Another thing Duchamp and Cage had in common is that they both died directly after dinner, which seems like a good time to choose. And that brings us to my fifth and final humanising factor, to accompany sex, pets, drinking and dissatisfied wives: death itself, the great leveller, which links all our names (including the handful who are still in the land of the living).

So the next time you come over funny at the Tate Modern or feel a little faint while reading an article, just remember: whatever name it is that is oppressing your brain, he or she was very probably sex-crazed, or a dog-lover, or a drunkard, or attached to a sceptical spouse. Failing that, they are almost certainly dead.