Where was the woman in white? With a growing feeling of nausea, the tousle-haired painter hurried through the gallery in search of her.

This was late spring of 1862. It was Varnishing Day at the Royal Academy, when artists learned if their pictures had been accepted for the academy’s prestigious show by seeing if they were hung.

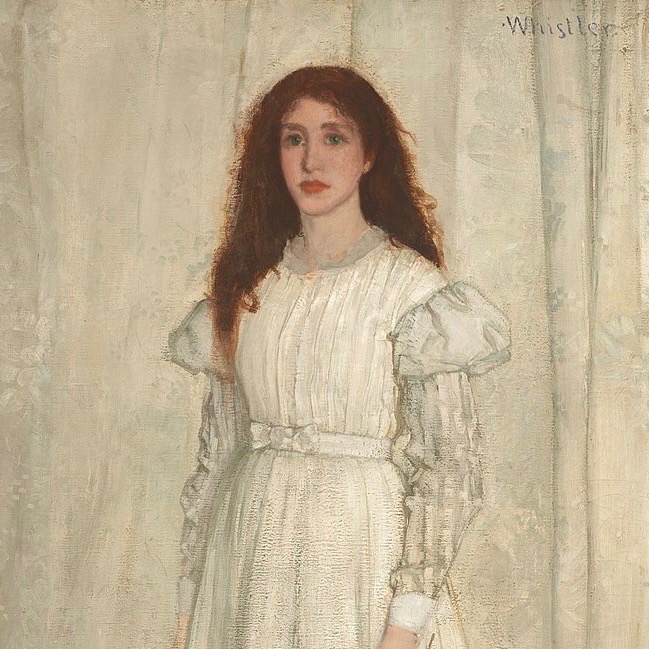

The American artist James Whistler, then 27, roamed the exhibition in vain. The work he had been looking for was his sensational — and sensual — painting of his flame-haired Irish mistress, Joanna Hiffernan.

‘I wandered on and on, through room after room,’ he recalled, ‘until I reached the last of them and knew she had been rejected!’

Now, a full 160 years later, his early masterpiece is about to be hung in the Royal Academy for the first time. Finally, the painting that is one of the most influential in the history of art is getting its just deserts.

As we shall see, it was rejected because Whistler brazenly defied the strict conventions of the day when creating it. But in doing so, he arguably produced the masterpiece that invented modern art and prompted the trend towards abstract painting.

It goes on display later this month at a Royal Academy exhibition exploring the contribution Hiffernan made to Whistler’s work. According to the curator Margaret MacDonald, the months spent during its creation took a brutal toll on the unmarried painter and his vivacious model, who shared his home in Chelsea.

Whistler’s friends thought his terrible temper might partly be the result of repeated exposure to the poisonous lead content in the white paint. The painter Dante Rossetti even wrote a limerick about it:

There’s a combative artist named Whistler

Who is, like his own hog-hairs, a bristler.

A tube of white lead

And a punch on the head

Offer varied attractions to Whistler.

As its name suggests, Whistler’s Symphony in White, No 1 — a 7ft tall picture of a woman in white, standing on a white rug, against a white background — required a lot of white paint. This, combined with solvent fumes, left the artist with stomach cramps, and the model, who had weak lungs, with a persistent cough. Then came the hammer blow of the RA rejection.

One can only imagine Whistler’s disappointment, not just because of the months spent on his masterpiece, but because of his deep emotional investment in the painting.

It was a love letter to his muse, who had captivated him with her passionate personality and her waterfall of auburn locks, which he called ‘the most beautiful hair that you have ever seen’.

The son of a railroad engineer from Massachusetts, Whistler first revealed his artistic talent at the age of four. As a young man, he travelled from America to Paris to study art, then to London where he met Hiffernan, an Irish girl who was working in the city as an artists’ model.

He was soon smitten and they began living together. His friend, the French painter Gustave Courbet, was taken with her too. He painted Hiffernan several times.

Indeed some have speculated she may have modelled for two of Courbet’s most outrageously erotic pictures, painted for Turkish diplomat Khalil-Bey who famously loved lubricious art.

In the first, Le Sommeil, a pair of lesbians lie naked in a post-coital swoon, presumably exhausted by their exertions.

In the second, L’Origine du monde, the startled viewer is greeted by a detailed and scrupulously realistic portrait of a woman’s vagina — one of the most scandalous works in the whole history of art.

Whistler’s painting Wapping comes closer to portraying this side of Joanna. Done between 1860 and 1864, it paints London’s docklands in Manet-like modernism.

Joanna — her identity betrayed by her auburn locks — is captured in conversation with two men, her back arched sensually against a railing over the river.

The painting oozes with sexuality, not only because of Jo’s alluring posture but because of the setting. Wapping was a hub for the British sex trade in the mid 19th century.

It has been suggested that Courbet and Hiffernan had an affair (because otherwise, obviously, he couldn’t have painted her so intimately in L’Origine du monde). And that this ended her relationship with Whistler in 1866.

But prior to that, the love between Hiffernan and Whistler was intense — it may even have been strengthened by the RA rejection. She described the RA judges as “duffers”. He reported soon afterwards that their picture, which was at first entitled The White Girl, would wear its rejection as a badge of pride.

He had agreed to let it be hung in a gallery in Fitzrovia. In the catalogue, it was marked ostentatiously as “Rejected at the Academy”.

“What do you say to that?” Whistler asked a friend. “Isn’t that the way to fight ’em?” He added that the catalogue listing amounted to “waging an open war with the Academy”.

In adverts, The White Girl was described as “Whistler’s Extraordinary Picture”. So what, exactly, was so extraordinary about it?

To understand this, it helps to know how the art world worked in the 19th century. At the annual Paris Salon, pictures were hung in groups according to five hierarchical categories. The best paintings, by definition, were thought to be history paintings; then portraits; then landscapes; then genre paintings (pictures of everyday life); and lastly still lifes (pictures of everyday objects). To succeed, you had to play the game, but that wasn’t Whistler’s way.

To present his picture as a portrait, he should have named it after the model. The fact he didn’t was a two-fingered salute to the art establishment.

Then there’s the way he made it. Whistler rarely did preparatory sketches, instead working out his ideas as he went. Among the new discoveries made by the show’s curator Margaret MacDonald and her colleagues, X-ray and reflectography reveal the changes he made to the work in progress (and continued making for years to come).

The look on Hiffernan’s face began as devout, eyes raised to heaven. But it was later altered, becoming increasingly vague and neutral. Moreover, Hiffernan’s arms hang at her sides, not in dejection, but with a total neutrality of expression. Whistler was defying critics to read narrative meaning into the picture.

In 1863 he submitted it to the Paris Salon. Once again, it was rejected. This time, though, there was such an outcry among artists about this and other notable omissions that word of it reached the ear of Emperor Napolean III, who duly endorsed the creation of a rival exhibition, which would bring together the best pictures that had been rejected by the Salon.

It was called the Salon des Refusés, and two of its pictures, Whistler’s The White Girl and Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, caused a particular stir. They were laughed at by the punters and praised by the enlightened. The show essentially gave birth to the avant-garde.

Thereafter, you could formally make a name not only by skilful conformity but also by challenging conventions. Manet’s painting is sometimes said to be the one that started modern art. Yet it is Whistler’s that, far more, prefigures the move towards abstraction that defined the next century.

While Whistler refused to paint a conventional portrait of Hiffernan, the dazzling new RA exhibition makes every effort to tell us what she was like.

The work of MacDonald and others dismisses outright the notion that Hiffernan appears in Courbet’s erotic works. Hiffernan was a redhead, unlike the woman in Le Sommeil (a blonde) or the woman in L’Origine du monde (a brunette).

Moreover, we now know that if anyone was unfaithful, it was Whistler. An affair with a parlourmaid in 1869 produced an illegitimate son, whom he ruefully described to a friend as “an infidelity to Jo”. For that to make sense, Hiffernan and Whistler must have still been together at the time. Extraordinarily, a few years later, Hiffernan herself, who was by then no longer living with Whistler, agreed to bring up the same child with the help of her sister Agnes.

Of all her discoveries, the one that “staggered” MacDonald most was that of the model’s death certificate. It had been thought she lived on into the 20th century. Yet it seems that the cough that had plagued Hiffernan in 1862, exacerbated by exposure to lead paint and solvents, returned in the 1880s, brought on by a particularly bitter winter. Hiffernan died of bronchitis aged 44.

There’s an irony here. In Whistler’s lifelong journey towards abstraction, his White Girl marked a crucial staging post. His decision to rename it Symphony in White, No 1 provides evidence of that. “As music is the poetry of sound,” he explained, “so is painting the poetry of sight.” He meant that, when thinking about art, the viewer should subtract, or abstract, the subject matter from consideration. Striving to create paintings that would make his argument for him, he went on to produce the notorious series of night scenes he called Nocturnes.

Having experimented with white, the colour of nothing, he now moved on to the darkness and fog of the world’s greatest city at night. Unable to cut ties entirely with realism, he was drawn to obscure sceneries, producing musically titled pre-abstracts that conveyed the “poetry of sight”. In the late 1870s, he enthused about that London weather, “They are lovely those fogs — and I am their painter!” Yet while they inspired Whistler’s most abstract and prescient paintings, it was those same dank, crushingly cold fogs that did for Jo.

***

.1. The fiery redhead. Whistler (1834-1903) met Joanna Hiffernan in 1860 and was blown away by the lustrous red hair of “the fiery Joe” (as his friend, the Trilby novelist George Du Maurier, dubbed her). “The most beautiful hair that you have ever seen!” Whistler raved. “A red not golden but copper — as Venetian as a dream!”

.2. Flower power. Hiffernan holds a sprig of white orange blossom, which symbolises purity. Discarded at her feet are other more colourful blooms, including violets and auriculas. The vision of a girl dispensing flowers recalls Millais’s doomed Ophelia (1852), while enacting Whistler’s aesthetic decision to reject other colours in favour of white.

.3. Inventing the abstract. Whistler’s loose brushwork was notorious, eventually leading to a courtcase after the critic John Ruskin accused him of “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Whistler sued — but won only a farthing’s damages. Yet as it turned out, he was on the side of art history, since his sketchy style pre-empted Impressionism.

.4. White on white. The artist’s decision to bet everything on white was a plea for composition over content. The critics refused. One said the painting obviously depicted a newly-wed, horrified at her loss of innocence. Another declared she was clearly the heroine of Wilkie Collins’s recent bestseller The Woman in White. Whistler replied, “I have never read it.”

.5. Facing the future. Whistler kept repainting Hiffernan’s face, making its expression vaguer and more neutral in a prefigurement of modernism. Unlike in William Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience (1953), say, it’s hard to guess what this woman is thinking.

.6. Dress to impress. Hiffernan’s dress is made of white cambric, a kind of lightweight linen. According to fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro, it has an arty simplicity that “contravened the contemporary fashionable look”, making a statement of its own.

.7. Taming the beast. Is it a wolf? Is it a polar bear? There’s no consensus, but critics have speculated that the snarling animal represents desire lying defeated at Hiffernan’s feet. Yet the red of its tongue picks up the red of her lips, hinting that there may be something else going on underneath the cambric.

.8. Perfect proportions. The front of Hiffernan’s right arm divides the width of the canvass exactly in two. The dividing line where the curtain ends and the carpet begins is precisely two-thirds of the way down the 7ft length. That creates a sense of harmony, yet at the same time it’s the bottom third that is more busy and colourful: a typical Whistlerian inversion of what you’d expect.