The Italian deserter stared at the dead sheep. It had been a strange decision of his to murder the livestock of the local priest. On the other hand, the man had grossly insulted him.

After fleeing from the Venetian garrison at Corfu, he had made it to the little village of Kassiopi in the northeast corner of the Greek island. There he flung himself on the mercy of the priest, who, learning he was Italian, slammed the door in his face. Hence the decision, in a fit of pique, to shoot the sheep. But now the bearded papa was ringing the church’s alarm bells.

Angry locals were approaching, bristling with guns, cudgels and pitchforks. Things were not looking at all good for our impulsive hero, whose name was Giacomo Casanova.

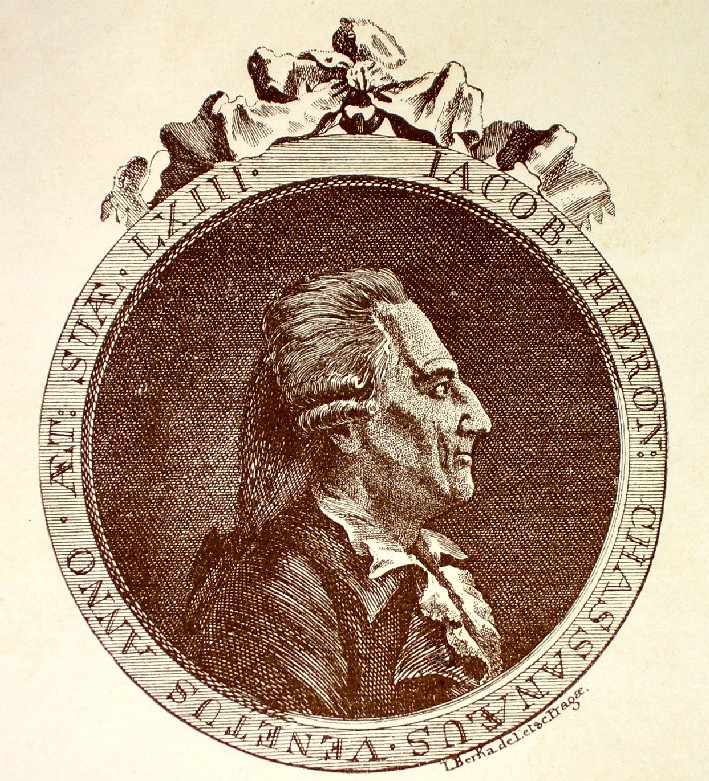

We have just passed the 200th anniversary of the publication of the great lover’s sprawling, hilariously self-congratulatory memoirs – a good time, in other words, to unearth this lesser-known episode in his eventful life. For the year he spent in Corfu reveals a surprising fact about Casanova. At the start of his long career as a ladies man, he was remarkably inept.

The oldest son of a pair of Venetian actors, Casanova was a delicate child who suffered from nosebleeds. Then, in his teens, he grew tall and handsome and discovered his vocation.

His earliest sexual encounters often ended badly, however. Once, he waited outside the bedroom of a girl he thought liked him, only for another boy to emerge and give him a kick in the stomach. On another occasion, a courtesan named Giulietta deliberately excited him, then slapped his face. On yet another, he caught gonorrhea from the wife of an Albanian soldier.

In his memoirs, while bragging about how many women he slept with – 136 by his count – he presents himself as their victim. “I was the dupe of women until I was 60,” he laments.

In 1744, aged 19, Casanova joined the army and went to Corfu. This strategically important island, which had been occupied by Venice for centuries, was often targeted by the Ottomans. Yet the 1740s were quiet. On arrival in Corfu Town, Casanova found his military duties were light. This left him free to pursue what by then he knew was his real interest.

And it was here, in Corfu, that he really learned how it felt to fail. After falling for a beauty named Andriana Foscarini, the young wife of a captain, he found himself floundering.

When I was in Corfu Town recently, I recruited a local expert, Antreas Grammenos, to help me work out the geography of Casanova’s struggles. This is challenging, since, despite the fact that, to this day, the Venetian-built town is probably the most beautiful city in Greece, Casanova doesn’t bother to describe it. He was always more interested in people than places.

Antreas told me the Foscarinis probably lived in military accommodation on the rock of the Old Fort, which sticks out into the sea in front of the town. It would have been at a dinner party here that Casanova suffered his first humiliation at Andriana’s hands. Asked to carve a turkey, he botched it. If he didn’t know how, she remarked, he shouldn’t have done it.

Casanova was furious. Soon afterwards, he discovered that she didn’t even know his name, although they had often dined at the same table. “I hated her,” he confesses.

Nevertheless, the lack of interest fired his passion. The young suitor channelled all his energies into entertaining her, convinced that, if he could make her laugh, the battle was half-won. By his own account – which is the only account we have – he succeeded spectacularly. On one occasion, he says, Andriana declared she hadn’t known it was possible to laugh so much.

At this juncture, however, he went and blew his chances with one of the explosive losses of temper that plagued his career. The episode was so strange, he cannot have made it up.

A disreputable Frenchman named La Valeur declared that he was a prince in disguise. Casanova knew this was nonsense, but to his dismay, everyone else accepted the story, not least the proveditore or military overseer. “They were so bored here, they were just glad to have a prince around,” Antreas told me. “They didn’t care whether it was actually true or not.”

Unable to endure the sight of the odious La Valeur being treated as guest of honour at the proveditore’s table, Casanova treated the man coldly. So La Valeur gave him a slap.

Outraged, Casanova controlled himself enough to quit the proveditore’s house and stalk across the drawbridge to the esplanade in front of town. There he waited. When La Valeur appeared, he beat him half to death with his cane. Then he walked to the coffee house on Eugenios Voulgaris Street and ordered a glass of lemonade without sugar, to match his mood.

Learning that he had been ordered to turn himself in, Casanova fled to the harbour and stole a rowing boat. From this, he jumped aboard another ship, which took him to Kassiopi.

This is where we came in. The sheep: dead. The priest: furious. The locals: increasingly threatening. So what did Casanova do? He threw money around—literally. By his account (and one has to keep using that phrase, when relating his implausible adventures), he had made a packet gambling in town, so his pockets were full of coins. He now scattered these like confetti.

The locals hesitated. They were intrigued. Soon Casanova had persuaded a group of them to act as his bodyguard. Moreover, since he needed clothes, he paid some pretty local girls to weave him some new garments. By his account—there’s that phrase again—he then bedded them one by one. Antreas, protective of the virtue of Greek women, doubts the story.

However, if we assume that Casanova did make it to Kassiopi, and encountered women there, it seems safe to say that he had a go. Back then, the place consisted of little more than a church and a few farmsteads. Now, in 2022, it’s a large seaside resort so popular with well-heeled British holiday-makers, it is sometimes referred to as “Kensington-by-the-Sea”.

Yet most of the young bucks, who lurk in Passion Club by the harbour and try to chat up the girls, are unaware that they are following in the footsteps of Giacomo Casanova.

In December 1744, after a pleasant fortnight in Kassiopi, Casanova received good news from town. La Valeur had been unmasked as an impostor. It was safe for him to return.

In town, he resumed his attentions to Andriana. Yet once again, the progress of the man whose name would become synonymous with seduction was to prove agonisingly slow.

He tried everything he could think of. Once, for instance, when she pricked her finger with a needle, he seized her hand and sucked the blood. Andriana was understandably taken aback. “Are you then a cannibal?” she asked. “I believe not, madam,” he shot back, “but it would have been sacrilege in my eyes if I had suffered one single drop of your blood to be lost.”

So much for gallantry. He arrived in Corfu in September 1744. Autumn became winter, and winter spring. Finally, in early summer, he achieved a kind of breakthrough.

After a period when Andriana had treated him with excruciating coldness, leaving him in a constant frenzy of outrage, he was informed that her husband wanted to employ him as his adjutant and that it had been Andriana’s idea. Moreover, if he took the job, his bedroom would be next to hers. Eagerly he accepted, convinced that she at last returned his interest.

Incredibly, though, he still struggled. When he tried to spy on her in her bedroom, he failed. When she had her hair cut, and he grabbed a tress as a keepsake, she spotted him. Casanova was apoplectic. She should have pretended not to notice, he insisted. Finally, Andriana took pity on him, discreetly giving him a parcel that contained an enormous lock of her hair.

It wasn’t obvious what to do with a yard and a half of female hair, yet to give the man his due, he was enterprising. He had some of it made into a bracelet. Some he fashioned into a necklace. Yet there was still some hair left. This he snipped very fine. Then he ordered a confectioner to mix it into a paste also containing amber, sugar and vanilla, and make sweets.

Casanova kept these in a crystal box, which he would produce with a flourish, before popping a sweet in his mouth. When Andriana asked, he was mysterious about the ingredients.

Ever since she had given him the hair, he had become increasingly open about his passion for her. She no more than tolerated this, until one day he threatened to kill himself. After so many months, she let him kiss her. He pressed his lips to hers for as long as he could without breathing. When she gently dissuaded him, he confessed the secret contents of his sweets.

After this, one might have assumed, it could only be a matter of time. So it seemed. But Andriana still insisted on taking things one step at a time—and there were many steps.

There was the time she was confined to bed after badly cutting her leg. Casanova, always fascinated by medicine, stooped and licked the wound, claiming his love was antiseptic.

June came. It was incredibly hot. Kisses gave way to embraces. Embraces developed into passionate rolling around. One night, when Casanova was on the point of combustion, Andriana lent him a hand – an act of mercy that she instantly followed with a long account of her romantic history. From girlhood, she said, she had been exeptionally sensual: “Love has always seemed to me the god of my being.” She married young, but was dismayed to find sex painful. So she and Captain Foscarini became “very good friends, but a very indifferent husband and wife”.

On the one hand, Casanova’s presentation of this episode is characteristically self-serving. Throughout his memoirs, he emphasises that women want sex as much as men. On the other hand, it’s evidence for a defence that is sometimes made of him: that he is genuinely interested in women. He listened. And his priapic honesty was better than controlling prudishness.

Ultimately, any attempt to defend Casanova is doomed. He is self-confessedly a terrible human being. The fact he admits it doesn’t absolve him. His vices are well catalogued.

Yet none of this prevents his memoirs, if taken in small doses, from being a fascinating read. First published in French in 1822, Histoire de ma Vie, which extends over 4,000 pages, offers an extraordinary insight into the fabric of life in the middle of the 18th century. They arguably provide the origin of the most cartoonish stereotype of the Italian male: childlike and charming, corrupt and passionate. And there’s a constant tension, which actually adds to the interest, as we try to work out which passages are true, and which pure fantasy.

When he praises his own courage and success, we should probably take it with a pinch of salt. When he comes across as clumsy or cowardly, we can assume he didn’t make it up.

Above all, it seems unlikely that he fabricated the ignominious ending to his extensive courting of Andriana Foscarini, which must, strictly speaking, be classed as a failure.

One night, after he had managed everything except total victory, she thrust him away from her with a cry of, “We were on the verge of ruin!” Beside himself, Casanova rushed from her bedchamber – straight into the arms of a local prostitute named Melulla. Casanova being Casanova, the way he describes the encounter is superbly slanted to his own advantage.

Melulla declared that, of all the Venetian soldiers, he was the one she most desired. When it was over, she refused payment, seemingly because he was such a magnificent lover.

Soon afterwards, Casanova learned that for, the second time in his life, he had gonorrhea. There the dream died. Even Casanova couldn’t consider giving his girlfriend the clap.

The result was, despite a year of trying, he never actually had sex with Andriana Foscarini. Understandably, after that, she rather went off him. In September 1745, a disconsolate Casanova returned to Venice and resigned from the army. It wasn’t for him. Apart from anything else, he had been passed over for promotion: the kind of slight he couldn’t forgive.

What, then, had he learned from his 12-month stay in Corfu? Helpfully, he sums up the lesson himself, returning to a theme that surfaces again and again in Histoire de ma vie, and which conveniently absolves him of all responsibility. Love, he says, is a madness. Love is a disease. And above all – particularly if you are Giacomo Casanova – love is irresistible.